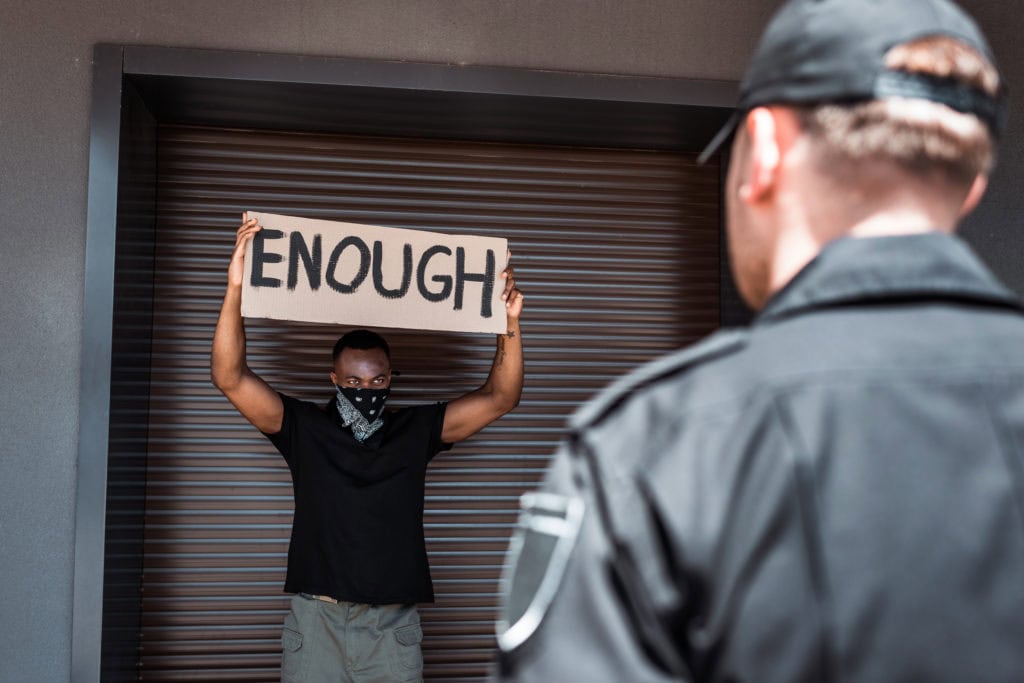

What Happens When The Police Breach Your Rights?

Every Canadian needs to understand his or her rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as well as how those rights can be enforced in a court of law. Once a court determines that your Charter rights have been infringed, there are remedies available to redress the wrong one has suffered. Criminal defence lawyers and other legal professionals refer to these legal outcomes as “remedies”.

Judicial Remedies for Charter Violations

Types of Remedies Available

Under the law, judges have the power to prescribe certain remedies when an individual’s rights have been violated. Various remedies exist, such as declarations, damage awards, restitution, and specific performance. In some instances, a Charter remedy could simply be a declaration that the government has indeed violated the individual’s Charter rights.

Damage Awards and Restitution

In rare cases, however, the court may order the government to pay the individual damages. Remedies like these, although, are not often available in criminal trials. During such trials, criminal defence lawyers argue the Charter with a very specific goal in mind – to exclude evidence or obtain a stay of proceedings. They argue that specific rights have been violated and aim for a remedy that will enhance their client’s position.

How Criminal Lawyers Use Charter Rights in Criminal Defence?

Criminal defence lawyers primarily use the Charter in two ways during a criminal trial:

First, to argue that the law their client has been charged with breaking is unconstitutional, and second, to argue that the investigation or arrest of their client was conducted unconstitutionally. Various remedies are available to the Court that respond to these lines of argument and further the defence lawyer’s ultimate goal of avoiding a client’s conviction. They can be found in sections 52, 24(1), and 24(2) of the Constitution Act of 1982 which contains the Charter.

In cases where a criminal defence lawyer presents arguments asserting that their client has been accused of breaching a law that itself is unconstitutional, they will seek redress under Section 52 of the Constitution Act of 1982. This rule establishes that if a law is non-compliant with constitutional provisions, and hence declared inoperative, the offence it created cannot exist in Canadian law. This implies that a court cannot adjudicate a person guilty of an offence that doesn’t have any legal standing. Accused individuals must be acquitted if an attorney can convince a court successfully of the unconstitutional nature of a law. Section 52 remedies, though, are not typically sought after in criminal proceedings.

The Morgentaler Case

Emulating this, check the exemplary R. v. Morgantaler case, where Canadian doctor and pro-abortion activist, Henry Morgentaler was acquitted after having been arrested for performing illegal abortions. Here, the Supreme Court of Canada declared the relevant law rescinded and of no force, which altered the course of Canadian law while freeing the accused.

In such cases, defendants often have potentially major implications at stake rather than just their personal freedom and are motivated to alter what they deem as unjust laws. This is mirrored in the R v. Malmo-Levine and R. v. Zundel cases, where defence arguments successfully invalidated the constitutionality of the laws connected to the possession of marijuana for medical purposes and spreading false news in the Criminal Code.

Leveraging Section 24 of the Charter in Defence Strategy

Despite the presence of this remedy, Section 24 of the Charter is more frequently used by criminal defence lawyers.

Understanding Section 24 of the Charter

Section 24 offers specific remedies to defendants if a particular act, attributable to the government during an investigation or prosecution, infringes on their rights. This section works in situations where the investigation or prosecution was inordinately unfair. It comprises two key remedies: under Section 24(1), a defendant may appeal to the court for any remedies the judge deems appropriate if their Charter rights have been violated. Under Section y24(2), an individual bearing the brunt of a rights breach can request the court to expel certain evidence from their trial.

Remedies Under Section 24(1)

Within the ambit of Section 24(1), if a defendant’s rights, guaranteed by the Charter, have been overstepped, they hold the right to apply to a competent court for a resolution that the court decides to be fair in the circumstances. This provision allows the judge significant discretion to choose an appropriate remedy but frequently, for those facing criminal charges, the most beneficial resolution manifested under Section 24(1) is a stay in proceedings.

Justified skepticism could remain around the possibility of the reintroduction of prosecution within a year, however unlikely. The Crown would only warrant the reinduction if extraordinary evidence against the defendant is procured eventually. It is accepted by legal minds as an end to prosecution and doesn’t proximate a criminal record.

Stay of Proceedings

If a defendant’s legal rights, established in sections 7 through 14 of the Charter have been dishonoured to a degree that would discredit the administration of justice, the court is expected to enforce a stay of proceedings under Section 24(1). Fulfilling the requirements of numerous acts of the charter could warrant alternate remedies under Section 24(1) that a trial judge can select after contemplation of factors that propel both the aim of the right under protection and Section 24(1).

Evidence Collection and the Ensuring of Charter Adherence

Section 24(2) provides a specific remedy related to Charter violations during the collection of evidence. If the defendant can show that evidence was gathered in a way that resulted in a Charter violation, they can request the court to exclude it from the trial under this section. However, this section does not follow a blanket exclusion approach after every Charter violation. The court will only exclude evidence under Section 24(2) where to do otherwise, would tarnish the administration of justice. There is a distinct guideline to ascertain whether evidence is to be admitted at the trial as given in R. v. Grant which is based on evaluating the seriousness of the state misconduct that violates the Charter, the impact of the breach on the defendant’s Charter-protected interests, and societal interest in case proceedings based on the actual happenings.

Under the Section 24(2) remedy, physical evidence, confessions, and biological samples like DNA and fingerprints may be excluded. Its chief purpose is to reinforce the reputation of the justice system in the eyes of the Canadian community. The court, with the application of Section 24(2), ensures that individuals are not convicted of crimes in scenarios where the state or its agents have blatantly disregarded the principles underscored in the Charter.

Jonathan Pyzer, B.A., L.L.B., is an experienced criminal defence lawyer and distinguished alumnus of McGill University and the University of Western Ontario. As the founder of Pyzer Criminal Lawyers, he brings over two decades of experience to his practice, having successfully represented hundreds of clients facing criminal charges throughout Toronto.